|

|

| Home |Software | Web Games | Quizzes | Free for Teachers | About | Contact | Links |

|

|

Attila the Hun

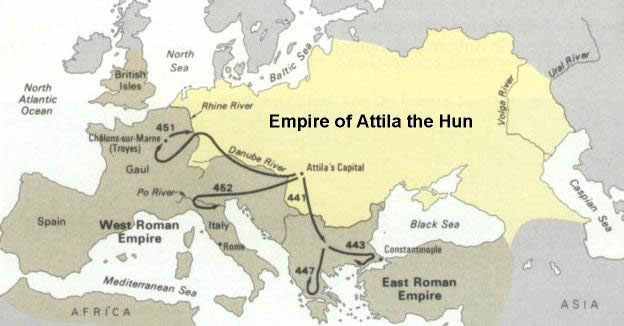

Attila the Hun (ca. 406–453 AD) was the last and most powerful king of the Huns. He reigned over what was then Europe's largest empire, from 434 until his death. His empire stretched from Central Europe to the Black Sea and from the Danube River to the Baltic. During his rule he was among the direst enemies of the Eastern and Western Roman Empires: he invaded the Balkans twice and encircled Constantinople in the second invasion. He marched through France as far as Orleans before being turned back at Chalons; and he drove the western emperor Valentinian III from his capital at Ravenna in 452. Though his empire died with him on the day of his marriage by choking on his own nosebleed, and he left no remarkable legacy, he has become a legendary figure in the history of Europe. In much of Western Europe, he is remembered as the epitome of cruelty and rapacity. In contrast, some histories lionize him as a great and noble king, and he plays major roles in three Norse sagas.

The Huns, led by Attila, invade Italy. From a painting by V. Checa.

The European Huns are often thought to have been a western extension of the, a group of nomad tribes from north-eastern China and Central Asia. These people achieved military superiority over their rivals (most of them highly cultured and civilized) by their state of readiness for combat, amazing mobility, and weapons like the Hun bow.

Attila was born around 406. Nothing certain is known about his childhood; the supposition that at a young age he was already a capable leader and a capable warrior is reasonable but unknowable. Following negotiation of peace terms in 418, the young Attila, at the age of 12, was sent as a child hostage to the Roman court of Emperor Honorius. In return, the Huns received Flavius Aetius, in a child hostage exchange arranged by the Romans. Most likely the empire schooled Attila in its courts, customs and traditions and in its luxurious lifestyle, in the hope that he would carry an appreciation of these things back to his own nation, thus serving to extend Roman influence. The Huns would probably have hoped that Attila would enhance espionage capabilities by the exchange.

By 432, the Huns were united under Ruga. In 434 Ruga died, leaving his nephews Attila and Bleda, the sons of his brother Mundjuk, in control over all the united Hun tribes. At the time of their accession, the Huns were bargaining with Theodosius II's envoys over the return of several renegade tribes who had taken refuge within the Byzantine Empire. The Huns, satisfied with the treaty, decamped from the empire and departed into the interior of the continent, perhaps to consolidate and strengthen their empire. The Huns remained out of Roman sight for the next five years. During this time, they were conducting an invasion of the Persian Empire. In 440, they reappeared on the borders of the empire, attacking the merchants at the market on the north bank of the Danube that had been arranged for by the treaty. Attila and Bleda threatened further war, claiming that the Romans had failed to fulfil their treaty obligations and that the bishop of Margus (not far from modern Belgrade) had crossed the Danube to ransack and desecrate the royal Hun graves on the Danube's north bank.

Attila and Bleda responded by renewing their campaign in 443. Striking along the Danube, they overran the military centers of Ratiara and successfully besieged Naissus (modern Niš) with battering rams and rolling towers—military sophistication that was new in the Hun repertory—then pushing along the Nisava they took Serdica (Sofia), Philippopolis (Plovdiv), and Arcadiopolis. They encountered and destroyed the Roman force outside Constantinople and were only halted by their lack of siege equipment capable of breaching the city's massive walls. Theodosius admitted defeat and sent the court official Anatolius to negotiate peace terms, which were harsher than the previous treaty: the Emperor agreed to hand over 6,000 Roman pounds (ca. 1,963 kg) of gold as punishment for having disobeyed the terms of the treaty during the invasion; the yearly tribute was tripled, rising to 2,100 Roman pounds (ca. 687 kg) in gold; and the ransom for each Roman prisoner rose to 12 solidi.

Atilla meets Pope Leo. Painting by Raphael.

Their desires contented for a time, the Hun kings withdrew into the interior of their empire. According to Jordanes (following Priscus), sometime during the peace following the Huns' withdrawal from Byzantium (probably around 445), Bleda died (killed by his brother, according to the classical sources), and Attila took the throne for himself. Now undisputed lord of the Huns, he again turned towards the eastern Empire. Attila demanded, as a condition of peace, that the Romans should continue paying tribute in gold—and evacuate a strip of land stretching three hundred miles east from Sigindunum (Belgrade) and up to a hundred miles south of the Danube. Negotiations continued between Roman and Hun for approximately three years.

As late as 450, Attila had proclaimed his intent to attack the powerful Visigoth kingdom of Toulouse in alliance with Emperor Valentinian III. He had previously been on good terms with the western Empire and its de facto ruler Flavius Aëtius—Aetius had spent a brief exile among the Huns in 433, and the troops Attila provided against the Goths and Bagaudae had helped earn him the largely honorary title of magister militum in the west. The gifts and diplomatic efforts of Geiseric, who opposed and feared the Visigoths, may also have influenced Attila's plans.

However Valentinian's sister Honoria, in order to escape her forced betrothal to a senator, had sent the Hunnish king a plea for help—and her ring—in the spring of 450. Though Honoria may not have intended a proposal of marriage, Attila chose to interpret her message as such; he accepted, asking for half of the western Empire as dowry. When Valentinian discovered the plan, only the influence of his mother Galla Placidia convinced him to exile, rather than kill, Honoria; he also wrote to Attila strenuously denying the legitimacy of the supposed marriage proposal. Attila, not convinced, sent an embassy to Ravenna to proclaim that Honoria was innocent, that the proposal had been legitimate, and that he would come to claim what was rightfully his.

Meanwhile, Theodosius having died in a riding accident, his successor Marcian cut off the Huns' tribute in late 450; and multiple invasions, by the Huns and by others, had left the Balkans with little to plunder. The king of the Salian Franks had died, and the succession struggle between his two sons drove a rift between Attila and Aetius. By the time Attila had gathered his vassals—Gepids, Ostrogoths, Rugians, Scirians, Heruls, Thuringians, Alans, Burgundians, et al.—and begun his march west, he had declared intent of alliance both with the Visigoths and with the Romans.

In 451, his arrival in Belgica with an army exaggerated by Jordanes to half a million strong soon made his intent clear. On April 7 he captured Metz, and Aetius moved to oppose him, gathering troops from among the Franks, the Burgundians, and the Celts. A mission by Avitus, and Attila's continued westward advance, convinced the Visigoth king Theodoric I (Theodorid) to ally with the Romans. The combined armies reached Orleans ahead of Attila, thus checking and turning back the Hunnish advance. Aetius gave chase and caught the Huns at a place usually assumed to be near Châlons-en-Champagne. The two armies clashed in the Battle of Chalons, whose outcome commonly, though erroneously, is attributed to be a victory for the Gothic-Roman alliance. Theodoric was killed in the fighting. Aetius failed to press his advantage, and the alliance quickly disbanded. Attila withdrew to continue his campaign against Italy.

Attila returned in 452 to claim his marriage to Honoria anew, invading and ravaging Italy along the way; his army sacked numerous cities and razed Aquileia completely, leaving no trace of it behind. Valentinian fled from Ravenna to Rome; Aetius remained in the field but lacked the strength to offer battle. Attila finally halted at the Po, where he met an embassy including the prefect Trigetius, the consul Aviennus, and Pope Leo I. After the meeting he turned his army back, having claimed neither Honoria's hand nor the territories he desired.

Whatever his reasons, Attila left Italy and returned to his palace across the Danube. From there he planned to strike at Constantinople again and reclaim the tribute which Marcian had cut off. However, he died in the early months of 453; the conventional account, from Priscus, says that on the night after a feast celebrating his latest marriage (to a beautiful Goth named Ildico), he suffered a severe nosebleed and choked to death in a stupor. An alternative to the nosebleed theory is that he succumbed to internal bleeding after heavy drinking. An alternate story of his death, first recorded eighty years after the fact by the Roman chronicler Count Marcellinus, reports: "Attila, King of the Huns and ravager of the provinces of Europe, was pierced by the hand and blade of his wife." The Volsunga saga and the Poetic Edda claim that King Atli died at the hands of his wife Gudrun.

Attila is known in Western history and tradition as the grim "Scourge of God", and his name has become a byword for cruelty and barbarism. Some of this may arise from a conflation of his traits, in the popular imagination, with those perceived in later steppe warlords such as the Mongol Great Khan Genghis Khan and Tamerlane: all run together as cruel, clever, and sanguinary lovers of battle and pillage. The reality of his character may be more complex. The Huns of Attila's era had been mingling with Roman civilization for some time, largely through the Germanic foederati of the border—so that by the time of Theodosius's embassy in 448, Priscus could identify Hunnic, Gothic, and Latin as the three common languages of the horde. Priscus also recounts his meeting with an eastern Roman captive who had so fully assimilated into the Huns' way of life that he had no desire to return to his former country, and the Byzantine historian's description of Attila's humility and simplicity is unambiguous in its admiration.

The historical context of Attila's life played a large part in determining his later public image: in the waning years of the western Empire, his conflicts with Aetius (often called the "last of the Romans") and the strangeness of his culture both helped dress him in the mask of the ferocious barbarian and enemy of civilization, as he has been portrayed in any number of films and other works of art. The Germanic epics in which he appears offer more nuanced depictions: he is both a noble and generous ally, as Etzel in the Nibelungenlied, and a cruel miser, as Atli in the Volsunga Saga and the Poetic Edda. Some national histories, though, always portray him favorably; in Hungary and Turkey the names of Attila (sometimes as Atilla in Turkish) and his last wife Ildikó remain popular to this day. In a similar vein, the Hungarian author Géza Gárdonyi's novel A láthatatlan ember (published in English as Slave of the Huns, and largely based on Priscus) offered a sympathetic portrait of Attila as a wise and beloved leader.

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the

Wikipedia article "Attila".